Continuing the Story of the Newman Art Supply Business (Part 2 of 3)

The story of the Newman logo and canvas stamp

Re-sharing this post because a reader brought it to my attention that the text was not showing up in emails and only in the Substack app. Please feel free to ignore if you’re already read this piece.

Good morning,

This newsletter continues my dive into the story of the James Newman firm which supplied fine art supplies for over 200 years to artists in England and beyond. If you missed the last installment, check it out here. In this installment, I’m exploring how the Newman firm developed a brand identity and the way in which product innovations by firms like Newman and other British suppliers promoted changing artistic practices.

James Newman’s Canvas Stamp & the Early History of Maker’s Marks

Newman emerged during a period in which the production of art supplies evolved from small-scale production to more industrial production geared towards national and international markets. In the history of artist supplies, the introduction of canvas stamps from the late eighteenth century signaled the shift from independent colourmen to organized firms that sold across markets. According to Alec Cobbe’s work on canvas stamps, one of, if not the earliest marking, is the stamp of James Poole of High Holborn, which is dated to 1799. As Cobbe explains, these stamps have been an invaluable sign for conservators and historians to date painting supports, thanks to variations in the “layout, size, lettering, changes of the firm’s address etc., and by recording their occurrences on dated paintings.”1 The National Portrait Gallery in London has documented British canvas, stretcher and panel suppliers’ marks across multiple works in their collection and recorded many of the stamps and marks for James Newman and his firm. Listed under Newman, there are 14 different marks that were used on canvases. Often, these marks were stenciled or stamped (fig. 1) directly onto the canvas or paper, although there’s at least two instances of the firm using paper labels.

The use of a distinctive emblem or watermark corresponds with the increasing prevalence of logos in the commercial world of the 19th century. These maker’s marks were historically done by masons, printers, jewelers and other trades people and guilds from at least the 13th century onwards in Europe. The history of such marks is possibly even more ancient. Frank Presbry in the The History and Development of Advertising, says that, “on bricks that were made by the Babylonians some three thousand years before Christ are found stenciled inscriptions which have been called the first advertisements.” Presby traces the later development of advertisement in Middle Ages England where town criers and doorway barkers competed for the attention of customers with cries like “What do you lack, master?”2 However, with the advent of the printing press, these cries gave way to tackups and public advertisements posted on walls. These advertising bills were called “Siquis,” which came from the Latin “Si quis,” which was how lost article notices would begin in ancient Rome. Another great advance in pictorial advertising showed up in England towards the end of the Middle Ages. According to Presbry, inns and taverns moved from displaying heraldic devices to pictorial signboards of animals like bulls and lions. Signs for more prominent inns and taverns were sometimes created by members of the Royal Academy, and according to Presby Correggio, Holbein and Watteau were all known to have painted signs. This increased attention to distinctive trade and commerce symbols precipitates the increasing sophistication with which businesses design marks for their products and packages. For businesses, this strategy helped unify multiple products under one single identity, to make clear that each product was not that of an individual craftsman, but belonged to that of a larger firm.

By placing their watermark on the canvases, Newman made a claim on the distinctiveness of their products, much in the way that an artist’s signature helped link a piece to an individual or studio and perpetuated the idea that there is something unique in the connection between maker and object. The Newman logo consistently used a Prince of Wales feathers trade mark at the center of its emblem from at least 1852 until its acquisition by Reeves in 1936. The emblem comes from the badge of the heir apparent to the British throne, the Prince of Wales. The badge's origins can be traced to Edward, the Black Prince, who had three ostrich feathers on a shield that was meant to symbolize peace. In terms of its usage by Newman, this trade mark may be a reference to a royal warrant; a framed sign in gouache in the Museum of London is evidence of an appointment to the Princess of Wales dating to 1815.3 Royal Warrants have been issued in England since the Middle Ages, and were given to tradesmen who supplied goods and services to the sovereign or other members of the royal court. In adopting this symbol, the Newman firm might have sought to capitalize on their appointment and signal to customers that they supplied the court and were thus a manufacturer that could be trusted, and perhaps even more importantly one that should be sought out for their superior quality.

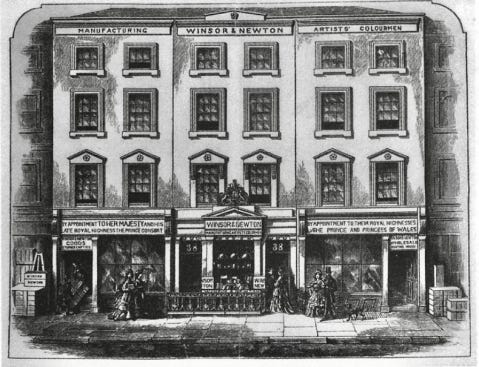

Another consistent feature in the Newman logo from the 1850s through the early 20th century is that the firm’s location in Soho Square in London is prominently called out. In fact, the logo says nothing about the company’s wares and entirely relies on the name and location to signal the brand. hen the brand was sold only in London, this would have been a helpful way of advertising its location. Other colourmen were set up along Rathbone Place (fig. 2), which is located directly above Soho Square, and was one of the prominent quarters for artists, colourmen, and other suppliers of the artistic professions. As early as the 1850s, there’s also evidence that the brand was sold outside the United Kingdom, in Paris, so this would have been a way of signaling a linkage to the colourmen of London. In fact, French colorman Giroux Alphonse, located at 7 rue Coq Saint-Honoré, and a notable supplier of the Barbizon school of painting advertised that he was the sole supplier of products by Newmans of London.4 This connection could have been advantageous to signal due to the prominence of British manufacturers in colors and specifically watercolor. These firms were at the forefront of color development, so indicating the London based aspects of the firm may have been a conscious decision to highlight the firm’s relation to British know-how in watercolors.

Advances in Watercolors

These advances were led by a small group of British firms that soon set the international standard for watercolors. A rival firm to Newman’s, Reeve, was responsible for the development of hard cakes of soluble watercolor (invented by William Reeves in 1780). Winsor & Newton followed with the innovation of moist watercolors in metal tubes in 1846. According to Elizabeth Barker of the Metropolitan Museum of Art “These machine-ground pigments produced fine homogeneous watercolors that set the international standard.”5 These developments were a huge improvement over the previous state of grinding pigment and mixing them by hand with a medium like gumwater. Part of the advances in color manufacture were thanks to the widening sources of plant gums from around the world that could be used as a medium. Importation records dating back to 1657 and through the 1851 attest to the variety of gums from Arabic to Senegal to Karaya which were brought into the UK thanks to the country’s extensive colonies and trade networks. Analysis by conservators shows varying amounts of gum and honey / sugar combinations used in watercolor cakes during the 19th century and may be further evidence for the level of experimentation in the industry and the drive to produce more long-lasting and vibrant watercolors for easy transport.

Although these firms supplied some of the leading professional artists of their time, much of their business was oriented towards producing for the burgeoning set of amateur artists. As Anthea Callen says, “Although the numbers training and working as professional artists had been increasing rapidly since the beginning of the nineteenth century, the decisive market for these new products was undoubtedly that of the amateur painter.”6 In this sense, there was an inextricable relationship between the development of more portable and usable artist materials and the rise of amateur artists. As materials became more accessible in terms of their use and price, more individuals, especially women of the leisure class, were drawn into creating art. There’s also a notable relationship between material advancements in art materials and the places that painters worked. Callen has documented this connection in her work the Art of Impression, which elaborates on how the development of portable paint tubes, watercolor cakes, and easels helped facilitate the rise of landscape painting, or plein-air, for professional and amateur artists in the 19th century. Firms like Newman’s helped facilitate the amateurization of painting as well as its expansion beyond the studio walls. The portal wooden watercolor kits developed by Newman allowed artists like Beatrix Potter to venture further afield and paint outdoors. Potter’s case is on the more luxurious end of what was offered. One of the most accessible models was a pocket-sized “Shilling color box” in Japanese tin. According to Barker, this was a Victorian bestseller, with more than 11 million units sold from 1853 to 1870.

From the stamping of canvasses to advances in watercolor technology, and the emphasis on portal and ready to use supplies, the 19th century proved a turning point in the art supply market from the independent colourmen who catered almost exclusively to the fine arts towards more commercially-oriented enterprises that sought to bring in new buyers who had the time and interest in developing hobbies and craft as part of their town or country leisure.

In the third installment, I’ll consider the catalogues and advertisements used by the Newman firm to increase awareness of their products.

Thank you for reading! If you’re interested in learning more about how Creissen Artistwear is reimagining historical artist’s clothes and wares, then please visit Creissen Artistwear on Instagram.

Resources Consulted:

Callen, Anthea. 2000. The Art of Impressionism : Painting Technique & the Making of Modernity. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Cobbe, Alec. “Colourmen’s Canvas Stamps as an Aid to Dating Paintings: A Classification of Winsor and Newton Canvas Stamps from 1839-1920.” Studies in Conservation 21, no. 2 (1976): 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1179/sic.1976.015.

Constantin, Stéphanie. “The Barbizon Painters: A Guide to Their Suppliers.” Studies in Conservation 46, no. 1 (2001): 49–67. https://doi.org/10.2307/1506882.

Presbrey, Frank. 1929. The History and Development of Advertising. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday.

Ormsby, Bronwyn A., Joyce H. Townsend, Brian W. Singer, and John R. Dean. “British Watercolour Cakes from the Eighteenth to the Early Twentieth Century.” Studies in Conservation 50, no. 1 (2005): 45–66. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25487717.

Cobbe, “Colourmen’s Canvas Stamps as an Aid for Dating Painting,” 85.

Presby, The History and Development of Advertising, 2.

See https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/research/programmes/directory-of-suppliers/suppliers-n for discussion of James Newman and early evidence for the firm.

Constantin, “The Barbizon Painters: A Guide to Their Supplier,” 54.

See Elizabeth E. Barker in her article “Watercolor Painting in Britain, 1750–1850” https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/watercolor-painting-in-britain-1750-1850

Callen, The Art of Impressionism, 4.