Potter's Paintbox and the story of James Newman (Part 1 of 3)

Researching the English manufacturer behind Beatrix Potter's paintbox.

One rainy morning in late March, I was in the Morgan Library & Museum with my parents and sister and wandered the exhibition Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature.

Seeing Potter’s illustrations brought back memories of flipping through the intricate watercolors showing Peter Rabbit’s adventures amidst a well manicured garden. What excited me even more was the chance to discover Potter’s exquisite watercolor landscapes of the English countryside and her precise studies of natural objects like shells. As we were about to leave the show, I caught a glimpse of Potter’s paintbox.

Looking at the box, I appreciated the balance of utility and craftsmanship. With its thin partitioned compartments for holding the tools of the painter’s trade and the elegant exterior in varnished mahogany with brass hardware for the keyhole and a ring pull drawer, the box seemed to me an exemplary product, of the type rarely seen today. I decided to seek out the manufacturer and learn how paint boxes like this were made. My first clue was an emblem on the inside face of the box’s top. The circular emblem said NEWMAN at the top, SOHO SQUARE ON the left, LONDON on the right, and the number 24 on the bottom right. The label card indicated that Potter had used the box as a teenager and that it contained a secret compartment that held notes on how to paint flowers using watercolor.

I quite liked this idea of a secret compartment for a paint box—a place for the artist to stash private creations and objects. In many ways, the creation of boxes like this one links to a broader historical development of new attitudes towards the objects of daily life. Between 1500 and 1800, furniture and objects like storage chests and boxes evolved from simple practical items to becoming objets d’art in their own right. Interestingly, this corresponds to a compartmentalization of the activities of daily life and an increasing valuation of private life. Since then, our society seems to have undergone another revolution in which the privacy of one's desk or dresser is no longer even considered in design. For example many modern desks do not even contain a drawer let alone a lock, since much of what is really valuable is stored digitally and protected with virtual locks [1]. Alas, I digress from Newman, but this notion of private compartments and the importance of the inner spaces of objects is one I’ll return to often in this newsletter.

The National Portrait Gallery keeps a well researched directory of British Artist suppliers from 1650 to 1950. The story of the Newman manufacturer begins in the 18th century, when James Newman (c. 1757-1835) a pencil maker took out an insurance policy for his business at 17 Gerrard St in London [2]. It's worth noting that a pencil maker then actually referred to a brushmaker, as brushes were called hair pencils and the word pencil itself comes from old French “pincel,” which means paintbrush.

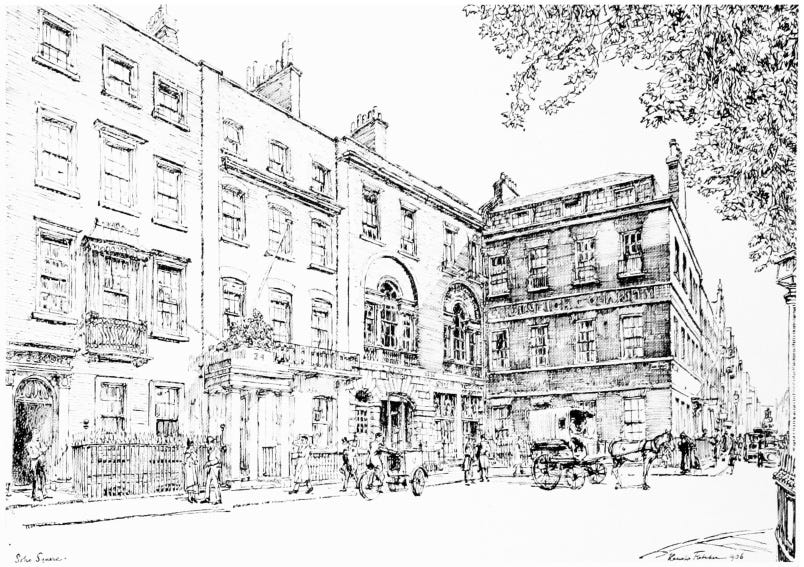

Newman progressed from offering brushes to becoming a known color manufacturer. In 1811 he was noted by landscape painter John Cart Burgess as being one of three manufacturers that had perfected watercolors. At some point in the 19th century he moved the business to 24 Soho Square where it remained until 1937. James Newman passed away in 1835 at the age of 78 and the business passed on to his son, also named James Newman, who seems to have been vigorous in defending the family business—there’s an 1840 record of an assault that he perpetrated against a rival firm at 14 Soho Square!

It seems that in the late 19th century the business was passed on to a certain W.F. Mills, who is described as the proprietor of Newman’s in a book on the history of Soho. The business endured until 1936 when it was purchased by another art supply firm Reeves, and forced to move from 24 Soho Square when the building was demolished in 1937. It seems that the brand survived in some capacity, although there’s no record as to when the Newman name was definitively no longer used by Reeves. My hunch is that the name was discontinued because artists no longer sought out Newman products by name, and instead sought out the Reeves name or rival firms like Winsor & Newton.

That concludes this brief sketch of James Newman and the firm behind Potter’s paint box. In the next installment, I’ll look more closely at the Newman logo, their products and catalogs, and patents.

Thank you for reading,

James

End Notes:

For more on this read shift in attitudes see Chartier, Roger, and Arthur Goldhammer. 1993. History of Private Life. Vol. 3, Passions of the Renaissance. Harvard University Press.

Simon, Jacob. “British Artists’ Suppliers, 1650-1950 - N.” British artists’ suppliers, 1650-1950 , March 2024. https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/research/programmes/directory-of-suppliers/suppliers-n.

Plate 70: Soho Square', in Survey of London: Volumes 33 and 34, St Anne Soho, ed. F H W Sheppard( London, 1966), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vols33-4/plate-70 [accessed 20 August 2024].

Lovely, well researched piece. Thanks for sharing.